Shodo Daisuki Episode 34

Shodo Daisuki Episode 34

About Hanging Scroll Mounting Styles! (Yamato Shitate Edition) [Calligraphy]

Shodo Daisuki – Episode 034

This time, the theme is “Yamato Shitate” (purely Japanese mounting)!! At the end, we also share key points to keep in mind when having a scroll mounted!

Shimauchi, a man who truly loves calligraphy, explains everything in depth!!

Shodo Daisuki Episode 34 – Video Overview

This video features an explanation of hanging scroll mounting styles by Shimauchi, who loves calligraphy.

In the previous episode, he explained “Bunjin Shitate,” a style that came from China. In this video, he gives a detailed explanation of “Yamato Hyogu,” a style that developed independently in Japan.

He introduces eight different hanging scroll formats, explaining their characteristics, uses, and historical background.

He first talks about the three basic modes of formality: shin, gyō, and sō, and explains that within these there are formats such as “shin-no-shin” and “shin-no-sō,” which differ in formality.

“Shin-no-shin” is the most formal, while “shin-no-sō” is slightly less formal.

He then goes into detail on “Yamato Hyogu,” a uniquely Japanese mounting style.

In particular, the three-section mounting with decorative hanging bands (sandansō with futai) is presented as the representative style, and he explains that it harmonizes beautifully with Japanese-style rooms.

He also touches on the historical origin of the futai (hanging bands), explaining that in China they were used to protect scrolls from birds and insects.

In addition, he explains “chakake shitate,” the mounting style used for scrolls hung in tearooms, noting features such as the very narrow side pillars and the unique structure in which the main paper of the work appears on the front of the mounting fabric.

Finally, he emphasizes three common points to watch out for when deciding on a mounting: considering the wall color and size of the place where the scroll will be displayed, paying attention to the width of the work, and ensuring that the work and the mounting fabrics harmonize well.

YouTube Shodo Daisuki Episode 34

Shimauchi 00:00

The fabrics are truly gorgeous, and there are eight named formats in total.

These formats were originally created to protect hanging scrolls, with the work mounted on them—and I imagine there are many people who don’t actually know that.

Hello, this is Shimauchi, who loves calligraphy.

Today’s theme is a continuation of hanging scroll mounting styles.

Shimauchi 00:22

This video is the second part on hanging scroll formats.

In the previous episode, I talked about “Bunjin Shitate,” which came to Japan from China.

This time, I’ll explain “Yamato Hyoso,” a style that developed independently here in Japan.

At the end of this video, I’ll also share some important, general points to watch out for when commissioning a hanging scroll,

Shimauchi 00:45

so please watch all the way to the end and don’t miss those key tips.

On this channel, I introduce not only calligraphy itself but also many topics related to writing,

Shimauchi 01:00

so please subscribe and give the videos a thumbs-up.

All right, let’s get into the main topic. I imagine that many of you watching this video practice calligraphy, but even aside from calligraphy pieces,

when you hear “hanging scroll,” there are probably certain common images that come to mind.

Shimauchi 01:21

One of those images is the three degrees of formality: shin, gyō, and sō.

You might think, “I’ve never heard that before—is it something like pine, bamboo, and plum?”

But within these shin–gyō–sō categories, there is actually another layer of shin–gyō–sō.

Shimauchi 01:42

At that point, it can feel like, “I have no idea what’s what anymore.”

Strictly speaking, there is no “sō-no-shin,” so in practice there are eight named formats.

It’s a bit complicated.

In this video, I’ll focus specifically on what these shin, gyō, and sō mounting styles are,

Shimauchi 02:02

and explain them in a concentrated way.

First, let’s talk about “shin.” This is the so-called “butsu-shitate” (Buddhist mounting).

It also has other names such as “shinsei hyogu,” “chūson hyogu,” or “honzon hyogu.”

These terms may sound unfamiliar, but please try to remember them.

Shimauchi 02:22

The works mounted in this style are Buddhist paintings, bokuseki, and other pieces related to Buddhism.

To give more familiar examples, you can think of images of Amida Buddha,

Shimauchi 02:38

or pilgrimage stamp sheets from the 88 temples of Shikoku, or the 33 temples of Saigoku.

Those kinds of works are often mounted in this Buddhist style.

The fabrics are very ornate, and the overall impression is rich and luxurious.

Shimauchi 02:56

Earlier I said that within the shin–gyō–sō formats there is another layer of shin–gyō–sō, and that in this context “shin-no-shin” is the highest in formality,

with “shin-no-sō” being somewhat less formal.

If you can remember it in those terms for now, that’s enough for this video.

Shimauchi 03:15

As you can see from the diagram, there are three distinct formats in this category—please just remember that much for now.

It’s also possible to choose mounting fabrics that match a specific Buddhist sect, so if you want to get that detailed,

Shimauchi 03:31

I recommend consulting with your hyogushi (professional mounter).

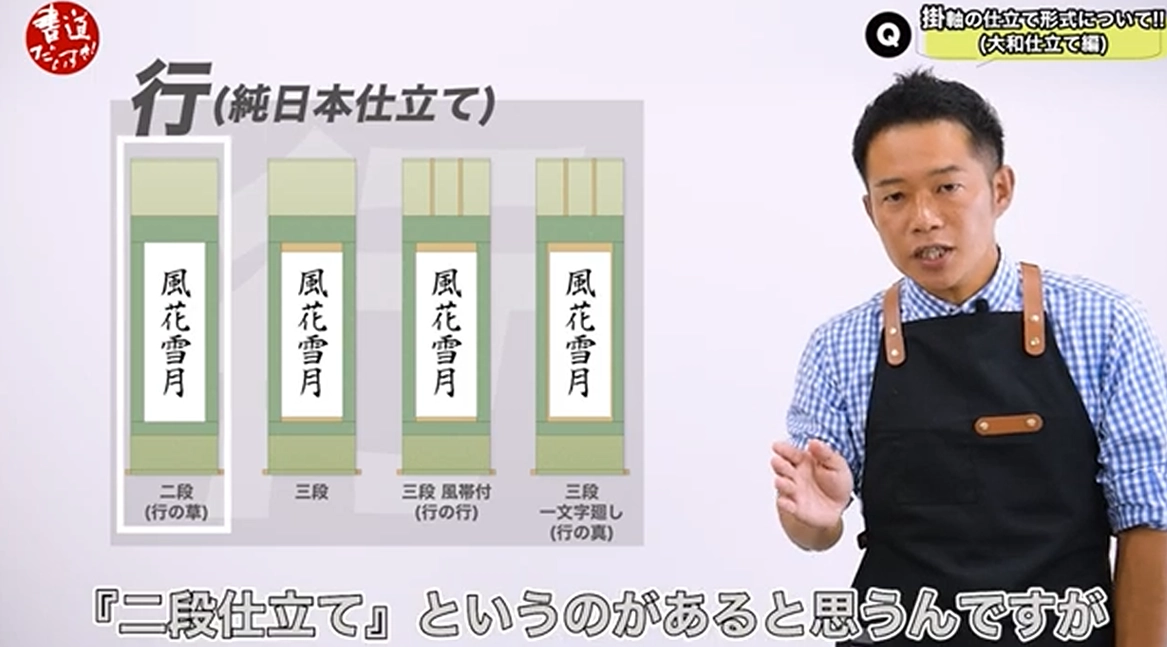

Next, let’s look at “gyō.” This is the “pure Japanese” mounting style.

The most representative format here is the three-section mounting with hanging bands (sandansō with futai).

I imagine many of you think of this format when you hear “hanging scroll.”

Shimauchi 03:51

This is a uniquely Japanese mounting style and harmonizes beautifully with Japanese-style rooms.

In terms of works, it suits Zen phrases, bokuseki, and paintings.

For paintings, subjects like landscapes, birds and flowers,

Shimauchi 04:10

or still lifes all go very well with this style.

Kana works also match this format nicely.

Even some kanji works can be used, depending on the content of the poem or phrase.

However, I must add one important caution: for Nanga (Southern School), literati painting, or works based on Chinese poetry and calligraphy,

Shimauchi 04:34

this format is not appropriate, so it is best to avoid it for those.

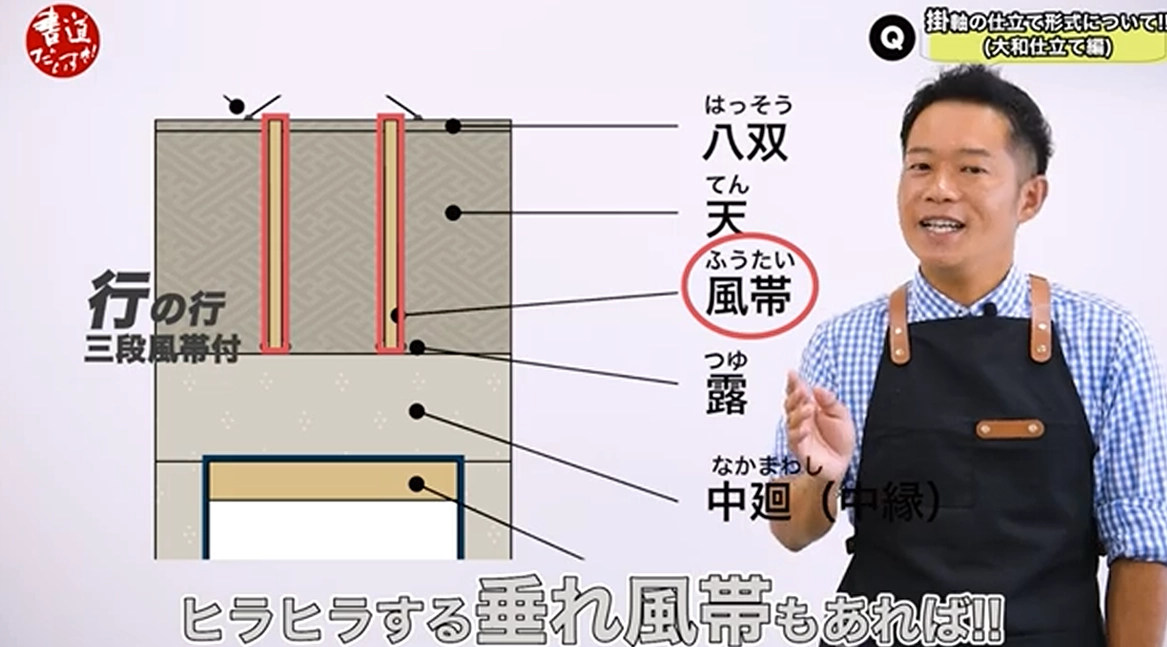

Now, to explain in a bit more detail, I’ll use the “gyō-no-gyō” format as our example.

Why is it called three-section mounting (sandansō)?

Shimauchi 04:50

Because at the very top you have the “ten” fabric, below that the “nakamawashi” fabric, and then the ichimonji strip at the bottom of the mounting section.

Counting from the top, you have one, two, three sections—hence “three-section mounting.”

Then there are the futai, the hanging bands. There are the long, fluttering “tare-futai,”

Shimauchi 05:10

the “oshi-futai” that lie flat against the surface, and even futai that are formed by lines only—“suji-futai.”

You might have wondered, “What are these futai actually for?”

Many people are probably curious about that.

Shimauchi 05:26

In fact, this element was passed down from China around, if I remember correctly, about the 10th century, the Song dynasty.

The format imported from China already had these hanging bands attached.

In China, they were called “kyōen” (startling the swallows),

Shimauchi 05:46

a name that quite literally describes their purpose.

Back then, hanging scrolls were displayed in large open plazas.

Buildings at the time didn’t have curtains

or glass doors like we do now.

Shimauchi 06:07

They were wide open, so when a scroll was unrolled, birds and insects would fly right in.

Of course, that would damage the scrolls, so they attached these hanging bands—the futai—

Shimauchi 06:24

and when they fluttered in the wind, birds were frightened and stayed away.

In other words, the futai were originally used to protect the hanging scrolls.

Shimauchi 06:38

Unfortunately, this practice died out in China around the 14th century, the Ming dynasty,

but in Japan we preserved it as a part of our own unique culture, and what remains today are these futai.

With the three-section mounting, the presence or absence of futai changes the impression quite a lot, so personally,

Shimauchi 06:56

when there are no futai, I sometimes feel the scroll looks a bit lonely.

Of course it depends on the work, but you can decide whether to use flat oshi-futai,

long fluttering tare-futai, or suji-futai made only of lines.

Shimauchi 07:09

I think it’s good to choose based on what best suits the piece.

Next, if you look at the diagram, you’ll see something called “two-section mounting.”

This corresponds to the “gyō-no-sō” format.

You may wonder why this two-section style is different from the three-section mounting.

Shimauchi 07:23

The idea is that when the three-section mounting feels a bit too flashy or busy,

the two-section mounting can be used instead.

Because it reduces the sections, it incorporates elements of bunjin hyogu (literati mounting).

Shimauchi 07:43

It’s still a Japanese mounting style, so of course it goes well with Japanese motifs.

But it can also suit literati-style or Chinese-style works.

That’s why the two-section mounting has its own significance.

Shimauchi 08:03

So please remember this difference—it allows you to choose according to the piece.

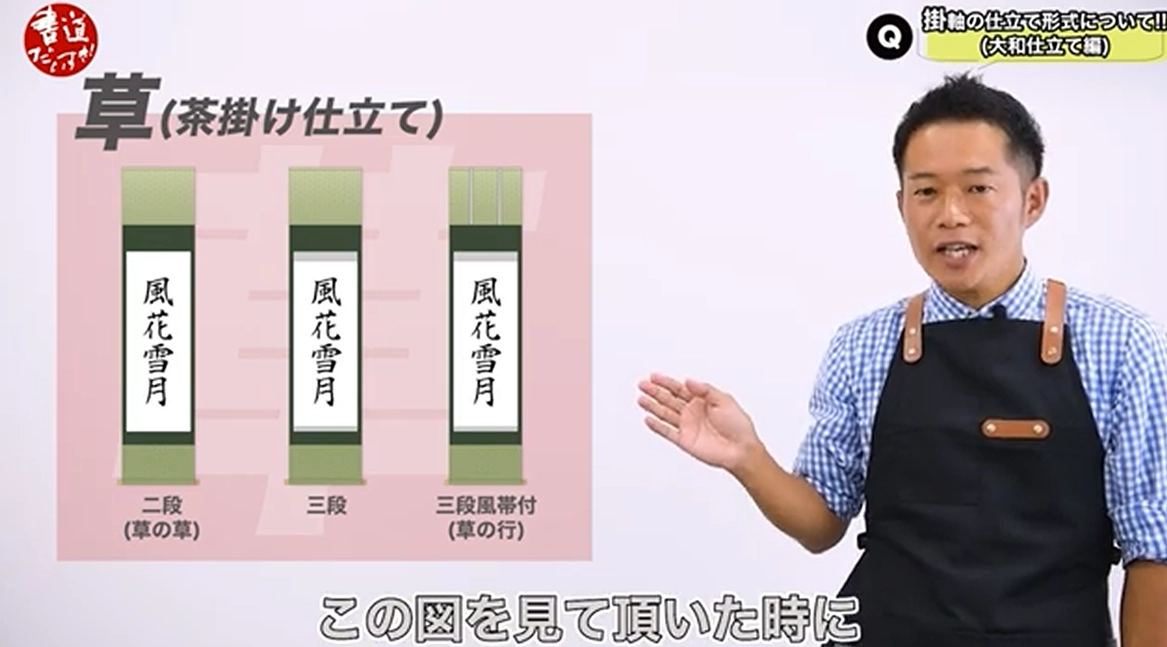

Next is sō, the chakake mounting.

As the name suggests, this is the type of scroll hung in tearooms.

Shimauchi 08:22

When you look at the diagram, many of you may wonder,

“What’s the difference between this and the three-section mounting?”

The key difference is that, compared to the three-section mounting, the pillar width here

is extremely narrow.

Shimauchi 08:45

Why are the pillars so narrow?

There’s a reason for that.

This format developed in the late Muromachi, Azuchi–Momoyama, and early Edo periods along with the tea ceremony.

If you think of scenes in historical dramas, for example,

Shimauchi 09:05

you’ll recall that tea rooms are quite small.

You might even think, “We’re going in through that tiny opening?”—that kind of cramped impression.

Naturally, the alcoves in such rooms are also small.

As a result, the works hung there also became small.

Shimauchi 09:21

And so, the pillar width became correspondingly narrow.

At the same time, the slender pillars also convey a message:

they show that the mounting plays only a supporting role,

while the work itself is meant to stand firmly at the forefront.

Shimauchi 09:42

When I say the work is “brought to the front,” I mean that in traditional chakake,

the main paper of the work actually sits on top of the mounting fabric.

In other words, the piece itself is mounted directly onto the front of the cloth.

Shimauchi 10:03

I imagine many people don’t know this.

However, if you say, “I know what a true chakake should look like, so please mount mine with the work on top like that,”

that’s fine in itself, but you have to keep something in mind.

Shimauchi 10:19

When you roll that kind of scroll up, creases and roll marks are more likely to form,

and the work is more prone to damage.

So please be aware of that, and if you still want to go with that traditional format, you can, of course.

Shimauchi 10:39

To avoid damaging works in that way, however, the mainstream today is to mount chakake in the same way as ordinary hanging scrolls,

with the mounting fabric overlapping the edges of the main paper.

Please remember that this is now the standard practice.

Shimauchi 10:59

In general, one can say that Yamato Hyoso formats are designed so that the scroll can be enjoyed

at a beautiful viewing length while seated.

For example, the ichimonji and the upper and lower mounting fabrics are proportioned so that the upper section is longer than the lower—

Shimauchi 11:20

a subtle but important design consideration.

I hope you’ll keep those points in mind as well.

Finally, I’d like to talk about three points common to both the Bunjin Hyoso formats introduced in the previous video

and the Yamato Hyoso formats introduced in this one—points to watch for when commissioning a hanging scroll.

Shimauchi 11:39

The first is to think carefully about where the scroll will be displayed.

Let’s use a tokonoma alcove as an example.

The background wall might be a pale green, or it might have an earthen-plaster tone.

If you choose mounting fabrics without regard to that background color,

Shimauchi 11:56

once you actually hang the scroll you may find that the colors clash and look unbalanced.

You also need to know the size of the place where the scroll will hang.

Modern alcoves are sometimes shorter than you might expect.

Shimauchi 12:15

If you mount a large tatejiku (vertical scroll) in a full Yamato three-section style,

the finished scroll can be about 210 cm long—over two meters.

So when you go to hang it, you may find the bottom of the scroll touching the floor.

Shimauchi 12:32

That’s something you definitely want to avoid.

If you know the size in advance, you can decide on the scroll length accordingly.

So that’s one point that absolutely needs attention.

The second point is the width of the work itself.

Shimauchi 12:49

The wider the piece, the more careful you need to be.

Let’s say you find a mounting fabric you really like—“I love this pattern, I want my scroll done in this!”

So you order the mounting with that fabric.

Shimauchi 13:07

When the scroll comes back, you might find that in an unexpected place,

the fabric has a seam where it was pieced together.

Why does that happen?

Because the width of mounting fabrics is predetermined.

Shimauchi 13:23

If the work is too wide, the fabric simply isn’t wide enough,

so the mounter has no choice but to add a seam.

If you’re okay with a seamed fabric, that’s fine as long as you understand it in advance.

Shimauchi 13:39

But if that worries you, then it’s best to have a careful discussion with your hyogushi beforehand.

That way, you can commission a scroll with peace of mind.

And finally, the most important point of all: leaving aside very special categories like Buddhist mountings or chakake,

Shimauchi 13:58

for most hanging scrolls it is not good for the work to overpower the mounting,

nor is it good for the mounting fabric to overpower the work.

What I’m trying to say is that the harmony between the work and the mounting fabrics is crucial.

Shimauchi 14:19

Only when they are in balance will people feel, “Ah, what a wonderful work, what a beautifully finished hanging scroll.”

If you can commission scrolls while being mindful of that harmony, that’s ideal.

Shimauchi 14:34

So please watch both the previous video and this one carefully, and when you feel, “I’ve created a really good piece,”

I’d be delighted if you would think, “All right, let’s have at least one really good hanging scroll made,”

for yourselves and together with me as well.

Shimauchi 14:49

This has been Shimauchi, who loves calligraphy. I’ll see you again on Friday. Goodbye!

Related Products

Here are the products that appear in this video.

```