Shodo Daisuki Episode 36

Shodo Daisuki Episode 36

The Shortest Route to Improvement!! How to Practice Correct “Keirin” (Classical Copying)

Shodo Daisuki – Episode 36

In this video, Shodo Daisuki’s host Shimauchi talks about how to practice “keirin” (form copying) the right way.

Shodo Daisuki Episode 36 – Video Overview

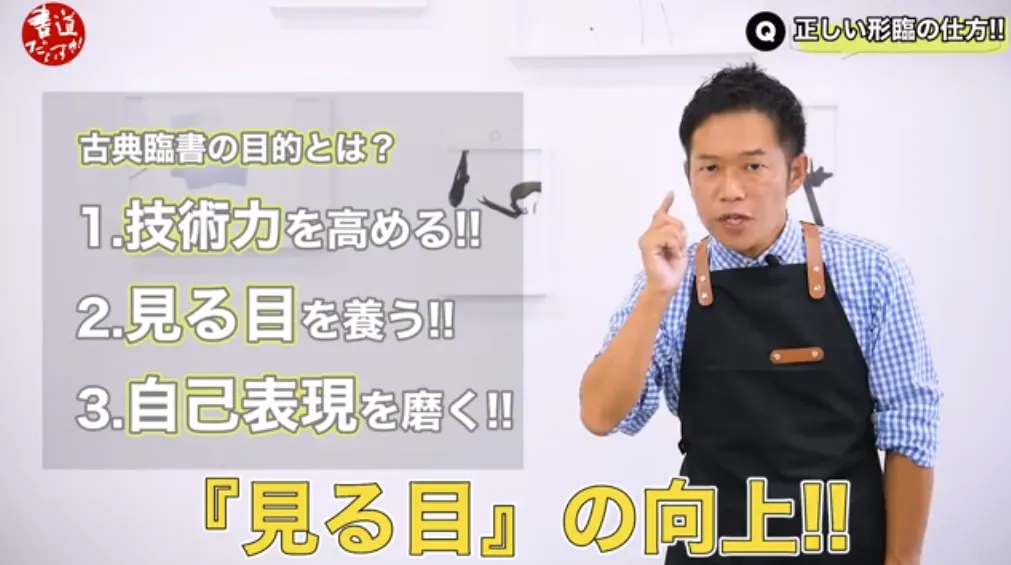

This lesson focuses on copying from the classics, especially on “keirin,” the practice of faithfully copying the shape of characters. “Rinsho” means carefully copying classical models, and Shimauchi emphasizes that it not only improves technique, but more importantly trains your “eye” for seeing well.

Through rinsho, your ability to appreciate works improves, you discover new things when looking at classics and completed pieces, and your own sensitivity and sense of beauty start to change.

For keirin, paper with minimal bleeding is recommended. Because your brush movements naturally become slower while you observe the model closely, you want a paper that doesn’t let too much ink soak in.

The classical methods of “sokō tenboku” (double-outline filling) and “kōji” (tracing each stroke) are also introduced. In sokō tenboku, you place thin paper over the original, trace the outlines, and then fill them in with ink; in kōji, you trace each stroke of the character in the original stroke order. Shimauchi especially stresses that practicing kōji makes you notice the fine structure and construction of each character.

In the latter half of the lesson, six characters are selected from “Kyūseikyū” and Shimauchi demonstrates keirin. He first studies the model carefully, analyzing the features of each character in detail, then actually writes them. He also shows how he isn’t satisfied with his first attempt, notices issues, and tries again.

Shimauchi says that although keirin is difficult, the more you look, the more enjoyable it becomes, as you keep making discoveries and your own writing changes. He also recommends comparing handwritten models by your calligraphy teacher with the original classical works as another effective way to study.

YouTube Shodo Daisuki Episode 36

Shimauchi 00:00

Your own sensibility will change. When you enlarge it to 310%, I think even your way of perceiving forms will start to change. What really interests me is this reality here. Yes… Hello, this is Shodo Daisuki, I’m Shimauchi. Everyone, did you watch the previous video?

Shimauchi 00:23

Today, we’re going to dig even deeper and make “keirin” the main theme. By doing rinsho, you can raise your technical level, train your eye, and polish your self-expression. This allows you to write works with attractive expression, rich lines, and an elegant presence,

Shimauchi 00:46

and for that, I’d like anyone who wants that kind of work to focus first and foremost on rinsho study. At the core of that rinsho study is keirin. Are you consciously practicing keirin? Today I’d like to go into detail about what keirin is.

Shimauchi 01:07

On this channel, we’d like to keep introducing not only calligraphy, but anything related to “writing.” Please subscribe to the channel and give us your feedback and rating. Now, let’s move on to keirin.

Shimauchi 01:24

When you’re told to “do rinsho, do rinsho, do more rinsho,” aren’t you often just following that flow without really thinking? Writing a lot of sheets is not everything; more than anything, quality is what matters most. I said this in the previous video, and I’ll repeat it again today.

Shimauchi 01:42

The effect of rinsho is not limited to technique. Above all, improving your eye for seeing—that is the most important part. I really want to say this again and again. Training your eye—this is the key. You know when you go to an exhibition venue, look at a work and think, “What on earth does this say?”

Shimauchi 02:02

Or perhaps, “I don’t really understand what’s good about this piece…”—that happens, right? When your powers of appreciation improve, you can objectively judge and evaluate not only your own work but also other people’s works.

Shimauchi 02:20

As your ability to appreciate grows, you discover new ways of looking at classical works and completed pieces, and you naturally find new goals and ideals for yourself. Above all, your own sensibility changes. This, in itself, is exactly the effect of rinsho—it broadens your decision-making and judgment.

Shimauchi 02:43

Then you’ll want to see more works, do more rinsho, and improve even more—your motivation will keep growing. This cycle, repeated over and over, is what accelerates your progress. Therefore,

Shimauchi 03:02

continuing rinsho study is not only essential for improving your technique, but also the shortest route to sharpening your eye for seeing. If you want to keep writing for a long time, building this foundational practice of rinsho is absolutely crucial.

Shimauchi 03:21

So I’d really like you to keep working at it consistently. Now, let’s get to the main topic: what exactly is keirin? Keirin means copying the form exactly as it is. You carefully observe every stroke angle and thickness, the spacing between strokes, and the white space inside the character,

Shimauchi 03:45

and then you faithfully reproduce them. So, what kind of paper is suitable for keirin? To put it simply: paper with little bleeding. When you want to carefully look at the model and do serious rinsho, your brush movements inevitably become slower.

Shimauchi 04:08

That means the brush stays on the paper longer, and more ink tends to soak in. To prevent that and keep your brush moving smoothly, it’s better to use paper that doesn’t let the ink bleed too much.

Shimauchi 04:22

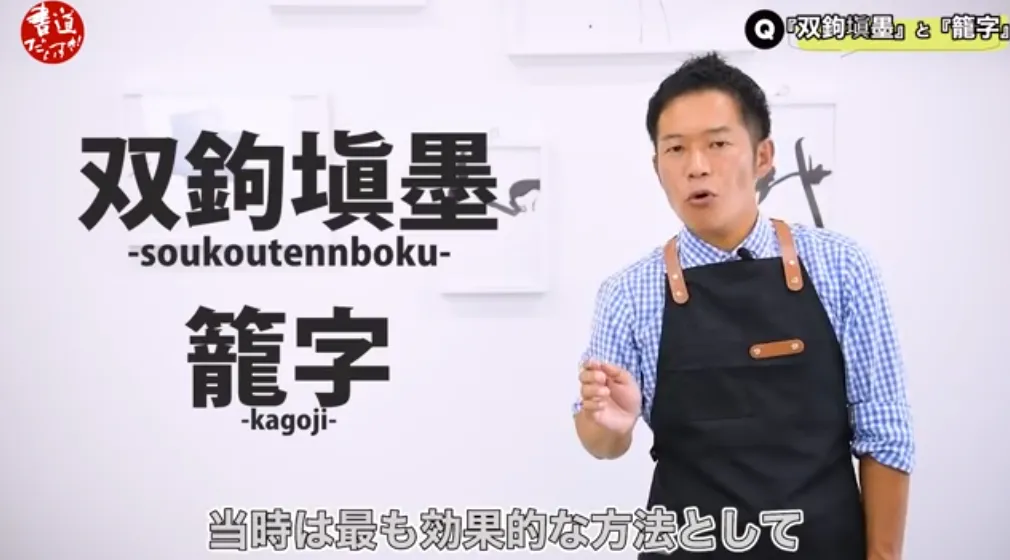

Even inexpensive machine-made paper is fine as long as it doesn’t bleed much. Instead, use that to practice a lot. Before we get into keirin itself, there’s something I’d like you to know: the methods called “sokō tenboku” and “kōji.”

Shimauchi 04:44

I imagine many of you are unfamiliar with these terms and think, “I’ve never heard those words before.” Don’t worry. These methods have long been known as some of the most effective ways to understand the shapes of characters.

Shimauchi 05:03

First, sokō tenboku. Sokō tenboku is a method that was developed long ago to duplicate characters written on paper. You place a sheet of thin paper over the characters. In this video, I used kana hanshi and tracing paper. When you do that, you can see the model underneath, right?

Shimauchi 05:23

Then you trace those outlines with a fine brush. It doesn’t absolutely have to be a fine brush—a pen is fine too—but this time I intentionally tried it with a fine brush. After that, you fill in the outlined area with ink.

Shimauchi 05:41

In this demonstration, I filled it in from the front, but there is also a method where you fill it in from the back. For clarity this time, I applied the ink from the front. It’s a way to create reproductions from the original. You can do sokō tenboku directly from the original, but the characters are often small.

Shimauchi 06:01

So, here’s where I tried something a bit different. I thought, “Why don’t we do sokō tenboku at hanshi size?”

Shimauchi 06:22

Look at this—I made this sheet by enlarging the original to 310%. It becomes this size. You can fit it neatly on a hanshi sheet and do sokō tenboku. For those who are motivated, it’s a lot of work, but being able to do sokō tenboku on hanshi is really worth the challenge.

Shimauchi 06:43

Before this method existed, reproductions were made through extremely precise hand copies. But that required a very high level of skill and naturally had its limits. So a more efficient method was needed—this is always how technological advances occur.

Shimauchi 07:09

Eventually, people started carving characters into stone or wood and then taking rubbings (takuhon) from them, establishing a new way of reproducing texts. That method of carving characters and taking rubbings spread widely as a way to make copies,

Shimauchi 07:28

and as a result, the older copying method of sokō tenboku gradually disappeared from common use. However, sokō tenboku is actually a very effective way to study calligraphy. It makes it easier to learn the structure of the characters and the tendencies of the style you’re copying.

Shimauchi 07:58

As a kind of “reliving history,” I’d really like you to try sokō tenboku at least once. To be honest, it was also my first time properly researching and trying sokō tenboku for this video.

Shimauchi 08:18

What I realized from doing it was that I could see clearly how the forms of the characters were actually constructed—there were a lot of new discoveries. That much is certain; no doubt about it. And, unexpectedly, I found it really fun.

Shimauchi 08:53

I’d like to add that. Of course, it did take a lot of effort and time. So in that sense, I’d also like to introduce another method: “kōji.” Next, I’ll explain this method of kōji.

Shimauchi 09:12

For kōji, the preparations are basically the same as for sokō tenboku. Earlier, we traced and filled the whole outline, but this time we trace each stroke one by one in the order they are written. This act of tracing,

Shimauchi 09:34

some people may feel it’s childish or resist it for that reason. But by doing kōji, the accuracy of your rinsho can change dramatically. Through kōji, you come to understand all the essential elements of rinsho: the shapes in the classical model, stroke angles,

Shimauchi 09:53

stroke thickness, and the white space within the characters—virtually every element you need. So when you encounter a classical text for the first time or decide to begin studying a certain classic,

Shimauchi 10:12

I definitely recommend that you try this method of kōji. Personally, I’m very glad I experienced it myself. In this demonstration I used a brush, but actually, it doesn’t have to be a brush—

Shimauchi 10:30

you can use a pencil or a pen, anything is fine. You can start right away. Kōji means tracing each stroke in order, correct? That means you can only imagine what the hidden stroke inside the overlapping lines looks like.

Shimauchi 10:50

You have to imagine how far that stroke extends and how it finishes. In other words, you’re imagining the entire process from how the brush touches the paper, moves, and lifts off. That act of engaging your imagination, I felt, also contributes to improving your technique.

Shimauchi 11:12

By tracing in this way, you start to see very fine details of the forms. In places you didn’t expect, you realize, “This part is actually quite large!” or

Shimauchi 11:29

“This stroke is actually much longer than I thought.” The view is completely different from when you simply write with a brush. So if you’re struggling with classical rinsho—if you feel you just can’t get it to look right—

Shimauchi 11:49

please try kōji. I think your keirin will change dramatically. Try it once, even if you feel skeptical—you’ll see that it’s really worth it. Now, I’d like to actually do some keirin myself. The classic I’ll be working from today is

Shimauchi 12:09

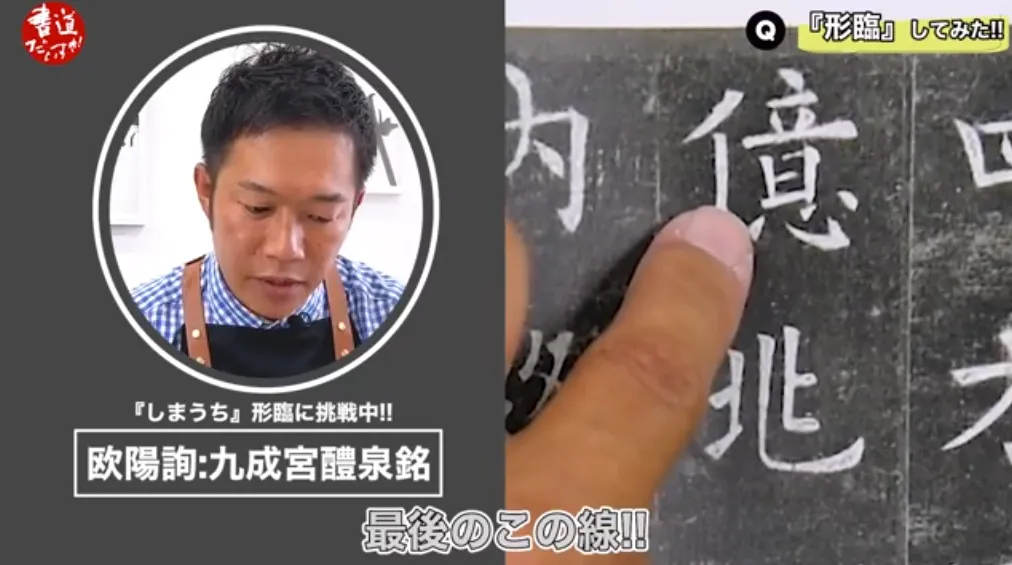

one of my favorites: Ouyang Xun’s “Kyūseikyū Reizenmei.” And the section I’ll be doing keirin of is these six characters here. This part. As I’ve said repeatedly, the important thing is to train your eye,

Shimauchi 12:31

so instead of jumping straight into writing, I’ll first carefully study this model. Let’s start with the first character, “oku.” For this character “oku,” overall, every stroke except for the second stroke of the “ninben” radical is quite long.

Shimauchi 12:50

That’s how it’s written. And this section here, this part turned out to be surprisingly large. That’s something I realized by doing kōji. Also, this last stroke here extends outward,

Shimauchi 13:10

whereas we tend to tuck it in when we write it ourselves. It’s something that’s easy to overlook, so I want to be careful about it. And then there’s this section where the brush first enters—

Shimauchi 13:27

the stroke begins very smoothly and gently without tension. I want to pay attention to that as well. In the component on the right, the center of gravity is shifted quite far to the left, so instead of aligning the center straight, we need to remember that the weight sits slightly left of center.

Shimauchi 13:43

Next, this character here, read “chō.” I actually didn’t know how to read it at first. When I checked the explanatory text, I realized, “Oh, this is ‘chō’!” That was another interesting discovery. And look at this—

Shimauchi 14:00

everything rises in a beautiful diagonal up to the right. It’s easy to miss this and accidentally make the long middle stroke the highest, so that’s something to watch out for. Next is this character “shi” (to begin). The first stroke of the “onna-hen” radical

Shimauchi 14:18

is surprisingly upright—almost straight. We tend to let it open to the left, so I want to be careful there. The “dai” component also has an exquisite shape and is very narrow and sharp,

Shimauchi 14:35

so we need to watch that; it’s easy to let it spread horizontally. Then we have the character “ji” (to hold). It leans quite a bit to the left, doesn’t it? And the third stroke, the dot,

Shimauchi 14:54

is almost a perfectly horizontal flick. For the character “fu,” what stood out to me most was the use of white space—there’s a very bold sense of openness inside the character. So I want to make sure it doesn’t become cramped, and

Shimauchi 15:12

I’ll be conscious of that white space as I write. The long sweeping stroke is especially difficult; I’ll try to pause slightly where it crosses the vertical stroke, gather strength in the line, and write it carefully. And this last dot is thicker and sits further inside than you might expect, so I’ll watch that too.

Shimauchi 15:30

Finally, this character “kō”—I feel it really shows the distinctive structure of this style. If you look closely at this horizontal stroke, it doesn’t show much “kishitsu,” the strong brush energy,

Shimauchi 15:49

and this leftward sweeping stroke really tilts the center of gravity to the left. There’s a generous pocket of white space here, and the left sweep is drawn almost vertically so it doesn’t awkwardly intrude into that space. As a result,

Shimauchi 16:10

the white space between the left and right parts of the character is really brought to life. We tend to want to tighten things up and make them compact, which often makes strokes stick too closely together, so that’s something I’d like to avoid.

Shimauchi 16:26

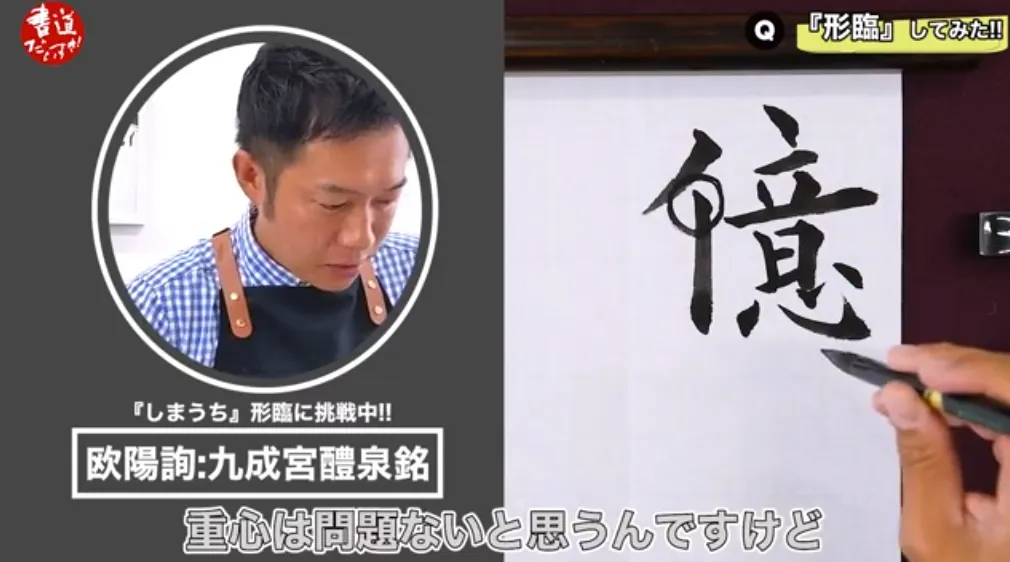

Even from just these six characters, there are so many things to notice. Once again, it shows that instead of writing blindly, it’s important to first form a clear image in your mind and then write with your brush. I’ll now try a keirin of “oku,”

Shimauchi 16:42

and if anything looks off, I’ll think about what could be improved and try again.

Shimauchi 17:16

Okay, so as you can see, it’s really hard to nail it in one go. What bothers me most is this part—this brush energy here.

Shimauchi 17:39

I think the overall center of gravity is okay, but the white space here turned out too narrow. Why? Probably because of the position of this stroke—it sits too low. In the original, it’s higher,

Shimauchi 18:03

so it should start around here and come out like this, leaving white space like this. We really needed to write it that way.

Shimauchi 18:32

When you think about it like that, you realize how difficult keirin is—but at the same time, the more carefully you look, the more enjoyable it becomes. There are constant discoveries, and your own writing changes in response.

Shimauchi 18:49

So I’d like to write it one more time. I think the “hi” component should actually be larger.

Shimauchi 19:06

To do really deep keirin, I think doing kōji thoroughly, as we mentioned earlier, leads to even more discoveries. Keirin really is profound—truly deep. But by sharpening your eye like this,

Shimauchi 19:20

I’m sure your technical skill will grow as well. So please don’t forget the importance of cultivating your eye and carefully observing your models. Many of you probably attend calligraphy classes. In that case,

Shimauchi 19:40

your teacher will study the classics and then write a handwritten model for you. Of course you should look carefully at that model, but it’s also very interesting to compare your teacher’s handwritten model with the original classic.

Shimauchi 19:59

You can see which parts of the original your teacher is focusing on. In a way, you’re making discoveries on two levels. Please keep that in mind. I hope today’s video has given you a sense of how deep keirin can be.

Shimauchi 20:21

Today we also touched on the old method of “rinmo” alongside rinsho. In Japan, copying has often been seen as something negative, but when it comes to accurately grasping the forms in classical models, it’s actually a very effective method.

Shimauchi 20:44

Rinsho can be practiced your whole life, but your ability to grasp forms tends to remain unstable. To master both structure and brush movement well, I believe it’s important to value both rinsho and rinmo.

Shimauchi 21:04

That’s what I meant when I asked, “Are you consciously practicing keirin?” I’d like you to take another look at rinsho, especially keirin, and I hope that will make your rinsho study even more enjoyable. Next time, we’ll talk about “irin” and “hairin.”

Shimauchi 21:21

This will be a challenge even for me, so I’d like to study it together with all of you. This has been Shodo Daisuki, Shimauchi. You can really feel the long autumn nights now, can’t you? I hope you all enjoy a wonderful weekend. Thank you for watching to the end.

Shimauchi 21:21

See you again next week! Goodbye!

About Related Products

Here are the products that appear in this video.

Books & Publications /book&publication

Whether you are a complete beginner just starting calligraphy or an intermediate to advanced learner, the knowledge you gain from books is invaluable.

They allow you to learn beyond your teacher’s exemplary works and are ideal for home practice or self-study.

Deepening your understanding of calligraphy through books will surely help broaden your horizons.