Shodo Daisuki Episode 37

Shodo Daisuki Episode 37

Controversial!? Shimauchi’s “Interpretive Rinshi” and “Back Rinshi”!! [Classical Copying][Calligraphy]

Shodo Daisuki – Episode 037

★☆★☆ Celebrating 1,000 Subscribers!! ★☆★☆

“Interpretive Rinshi” and “Back Rinshi” — topics that surprisingly don’t get discussed very often!!

This episode is once again passionate and easy to understand!!

Shodo Daisuki Episode 37 – Video Summary

Shimauchi gives a lecture on calligraphy, focusing especially on the concepts and methods of “rinsho” (copying classical works).

The lecture highlights two major rinsho techniques: “Keirin” (literal copying) and “Nyūrin” (interpretive copying), explaining their characteristics and how they are practiced.

At the beginning, Shimauchi expresses gratitude to viewers for surpassing 1,000 channel subscribers.

He then reviews the “Keirin” method introduced in the previous video—copying a model exactly—and moves on to explain the main theme of this episode: “Nyūrin.”

“Nyūrin” is described as a rinsho method in which you learn about the creator of the work and its historical context, allowing you to approach the classic with deeper understanding.

Using Wang Xizhi’s “Lantingxu” as an example, Shimauchi emphasizes how knowing its background enriches the quality of rinsho.

He explains that he once misunderstood “Lantingxu” as merely a record of a banquet, but later learned that it documents a sacred ritual — a realization that added depth to his rinsho practice.

Shimauchi also mentions the calligraphy of Kūkai and Saichō, noting that understanding how deeply they studied Wang Xizhi's works leads to deeper interpretation and expression.

He refers to “Nyūrin” as “expressive rinsho,” proposing his unique interpretation that even attempting to write without looking at the model can be a form of Nyūrin.

He shares his own attempts at both “Keirin” and “Nyūrin,” explaining the differences and new discoveries he encountered.

In conclusion, he emphasizes that the ultimate purpose of classical rinsho is “to express characters that only you can write,” and encourages viewers to continue rinsho to develop technique, sensitivity, and imagination.

YouTube Shodo Daisuki Episode 37

Shimauchi 00:00

A wild drinking party? Not at all.

I think what’s written here is actually something amazing.

Rinsho becomes even more fascinating than before.

By simply making that kind of practice a habit, we are really doing it “to express characters that only we ourselves can write.”

Hello, this is Shimauchi, and I love calligraphy.

Shimauchi 00:20

In the last video, I talked about Keirin.

This time, as the next step up, I’d like to introduce my own interpretation of Nyūrin.

Some people may think, “I haven’t even mastered Keirin yet, and now Nyūrin? That’s impossible…”

Shimauchi 00:36

But rather than backing away and saying, “No way, I can’t do that,”

I’d like to share my way of thinking. By understanding this interpretation, I truly believe your rinsho practice will become much more enjoyable.

So I hope you’ll watch this video with the mindset of “I’m going to give this a try!”

Shimauchi 00:55

On this channel, I introduce not only calligraphy but also many things related to writing and expression, so please subscribe and give the video a like.

And everyone, I’m sorry this took so long to say, but… Shodo Daisuki has finally reached 1,000 subscribers!

Shimauchi 01:13

Thank you so much! It’s truly all thanks to you.

I’m sure my partner behind the camera is really happy too—he’s probably grinning right now. Thank you from the bottom of my heart.

Shimauchi 01:24

I’ll keep working hard from here on out, so please continue to support me.

Now then, let’s dive into Nyūrin itself.

So, about Nyūrin. But before that, as I explained in detail in the previous video, Keirin—

Shimauchi 01:42

Keirin is the practice of copying the model exactly as it is.

By doing that, we improve our technical skill, and most importantly, we sharpen our sensitivity—that’s what I emphasized before.

You could call Keirin a form of “realistic rinsho,” right?

Shimauchi 02:02

Nyūrin, on the other hand, is about imagining the author’s intention and then placing more weight on adding your own expression to it.

You could call it “expressive rinsho” or “impressionistic rinsho.”

Let me use an analogy from music to make this easier to understand.

Shimauchi 02:22

Now, I wouldn’t say I’m particularly knowledgeable about music—

definitely not to the level of calling myself an expert—but when it comes to Japanese music, or “hōgaku,” I can of course understand the lyrics because they’re in Japanese.

Naturally, that means I can grasp the background and meaning behind the words as well.

Shimauchi 02:39

It’s easy to visualize the scenes described in the lyrics, right?

So when you sing those songs yourself, it’s easier to put your emotions into them.

In other words, it’s easier to express yourself.

On the other hand, when it comes to Western music—

Shimauchi 02:55

The melodies are cool and catchy—I can appreciate that too.

Even I can feel that, but because I don’t really understand the language, the lyrics themselves are unclear.

Shimauchi 03:08

So it’s hard to know exactly what they’re trying to express.

In other words, the background is unknown to me.

Because of that, if I were suddenly asked to sing both a Japanese song and an English song, there would be a big difference in how much of my own feeling I can put into each one.

Shimauchi 03:22

Not just a small difference—a big one.

Bringing this back to Nyūrin, Nyūrin is about learning as much information as you can about the author of the work, and the era and background in which the piece was created.

In other words, you are constantly gathering more and more information.

Shimauchi 03:39

By doing so, your knowledge of the classics deepens,

and you gradually walk closer to the classical works themselves.

That kind of “approaching the classics” mindset is extremely important in Nyūrin.

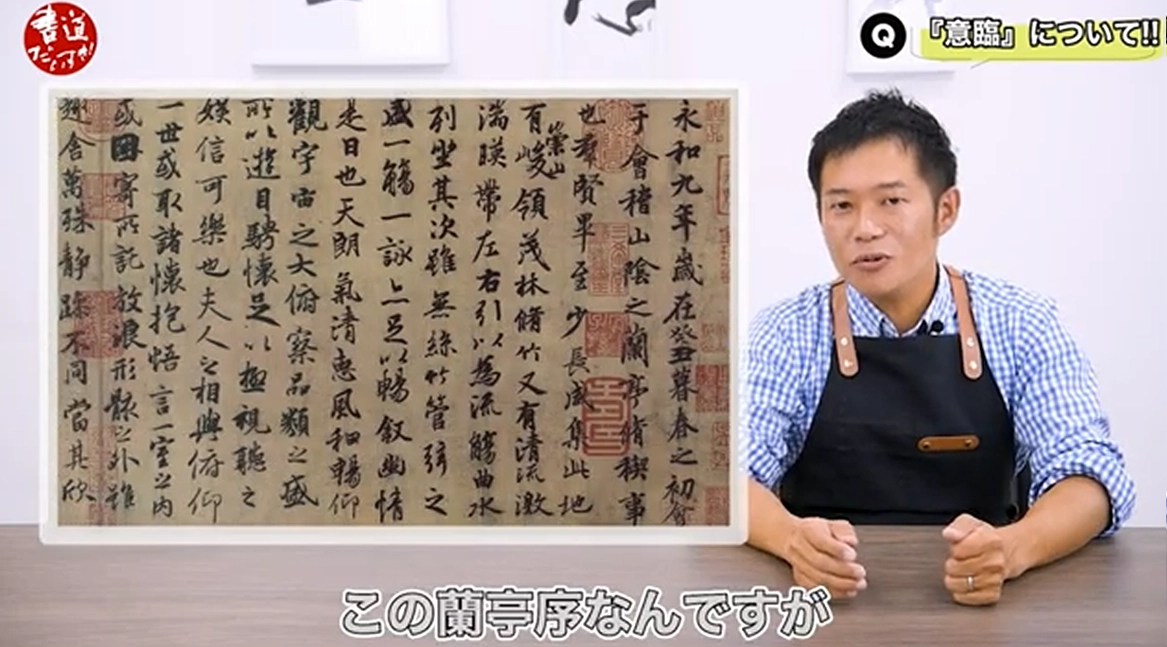

For example, let’s take a piece of classical information I know—Lantingxu.

Shimauchi 03:57

Regarding the “Lanting Preface,” I actually had a bit of a mistaken interpretation at first.

I used to imagine it as a kind of fun riverbank banquet: wine cups floating along a stream, people drinking and composing poetry, making merry while writing on the spot.

Shimauchi 04:16

I thought it was something like, “Wow, this is fun, this is great,” and that he just jotted down the lively scene in a sort of spontaneous way—so I assumed that’s why some parts looked a bit dense and filled in here and there.

That had been my image of Lantingxu.

Shimauchi 04:28

But when I actually did some proper research on Lantingxu this time, I found out that that image of a noisy party was completely off.

In reality, it describes a purification ritual where participants cleanse themselves and then offer their prayers to the gods.

Shimauchi 04:43

Around forty or so wise and virtuous people—people praised as sages—gathered there.

Each of them was to compose a poem before the sake cup floating down the stream reached them.

They would then recite their poems—elegant, refined verses full of grace.

It was a very noble and tasteful gathering.

Shimauchi 05:03

A collection of the best poems composed there was later compiled into an anthology.

And it’s said that Wang Xizhi wrote the preface to that poetry collection—that is the “Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion,” or Lantingxu.

From here on, this is my own imaginative interpretation, but—

Shimauchi 05:22

I like to think that Wang Xizhi wrote it in a state of excited joy, thinking, “Ah, that gathering was truly wonderful.”

So when you do rinsho of Lantingxu, rather than frowning and thinking, “This is so difficult…,”

I believe it’s better to return to Wang Xizhi’s feelings of “This is so delightful and fun,” and try to relive that joy in your own way.

Shimauchi 05:38

By having that kind of experience and then writing,

you can, I think, come just a little bit closer to Wang Xizhi.

To approach Wang Xizhi and do rinsho in this way—that is what I personally consider a form of Nyūrin.

Shimauchi 05:58

Next, another classical example I know is Kūkai’s “Fūshinchō” and Saichō’s reply letter.

Please take a look at these for a moment.

Although they’re letters exchanged between Saichō and Kūkai, even in these, you can clearly see how deeply they had studied Wang Xizhi’s calligraphy.

Shimauchi 06:19

They thoroughly absorbed the classical style and yet each established it as their own writing.

In other words, they fully digested the classical models and made them their own.

I think that’s something truly amazing.

Shimauchi 06:35

Now, how does this story connect to Nyūrin?

For those of you currently studying Fūshinchō, I’d like you to once again turn your attention to Wang Xizhi’s works.

Kūkai studied Wang Xizhi from a young age,

Shimauchi 06:55

and even traveled to China to pursue that study further.

Earlier I said, “Try to put yourself in Wang Xizhi’s shoes and do Nyūrin,” right?

This time, by learning the historical fact that Kūkai rigorously studied Wang Xizhi, we can also do Nyūrin based on those real events and background.

Shimauchi 07:15

By repeatedly engaging in this kind of Nyūrin,

we can experience a variety of “vicarious experiences” through the classics.

And I believe that in doing so, the scope of both rinsho and creative work expands, and rinsho itself becomes much more interesting.

Shimauchi 07:36

Next, I’d like to talk about “Irin,” which is said to be the ultimate form of rinsho, and also the stage you might want to tackle after Keirin and Nyūrin.

“Irin” can be thought of as a highly expressive form of rinsho.

That said, many people feel that Irin is extremely difficult and far out of reach.

Shimauchi 07:57

Some teachers might even say, “You’re a hundred years too early for Irin!”

But I’d like to strip away all those intimidating ideas and, in my own very expanded interpretation, share something simpler.

Many of you are already working hard on classic rinsho every day, right?

You’re focusing on Keirin and Nyūrin as you practice.

Shimauchi 08:14

So at the very end—after you finish your regular practice—try this: set the model beside you, but write one sheet without looking at it.

I think that alone is great.

Then look honestly at what you’ve written and compare it with the model.

Realizing, “Wow, it’s this different,”

Shimauchi 08:32

that awareness itself, I believe, already qualifies as a form of Irin.

I actually tried both Keirin and Irin myself.

In Keirin, I carefully watched the model as I wrote.

So I think my character sizes were fairly unified and I paid attention to the margins too.

Shimauchi 08:51

Even so, when I compared my work with the model, there were still plenty of differences.

Then I tried Irin: after finishing Keirin, I wrote again without looking at the model.

And, as you might expect, I really wanted to write the characters of “Kyūsei Kyūreisen” as cool as possible, so that desire came out very strongly.

Shimauchi 09:11

Because of that, the characters ended up a bit larger,

the strokes got bolder, and the margins felt somewhat narrower.

However, that strong desire to “write something really cool”

Shimauchi 09:27

showed up clearly in the energy of the brushstrokes, I think.

And for some characters, I felt I was able to write them in a form fairly close to the ones I had done in Keirin.

So in that sense,

Shimauchi 09:40

I feel that, as an Irin of “Kyūsei Kyūreisen,” that result is perfectly fine.

Just from trying this myself, I was able to make all sorts of discoveries and do a lot of reflection.

So I hope that when you work on classic rinsho,

Shimauchi 09:56

you’ll also challenge yourself to “write once without looking at the model” at the very end.

Just by making that kind of challenge a habit, I think things will change dramatically, so I would be very happy if you’d give it a try.

Now then, we’ve spent three episodes talking about rinsho,

Shimauchi 10:12

How did you like it?

When I talked about Nyūrin, I used the analogy of music, didn’t I?

Even with just a song’s lyrics,

the way I felt about them as a high school student and the way I feel about them now, in my forties, are completely different.

Shimauchi 10:29

There were songs I didn’t really understand back then,

but now they resonate deeply with me.

I’m sure many of you have had similar experiences.

And I think the same can be said when you apply this to classical rinsho.

Shimauchi 10:45

The way you perceive rinsho when you’re young,

and the way you perceive it now, after gaining more life experience, are likely very different in terms of feeling and sensitivity.

So rather than thinking, “I already did rinsho of this classic long ago, so I’m done with it,”

Shimauchi 11:06

I’d like you to revisit those classics again now, precisely because you’ve grown and experienced more in life.

I’m certain that you’ll rediscover new aspects of classical rinsho that you couldn’t see before.

Shimauchi 11:23

Above all, please don’t forget this one thing: the ultimate goal of classical rinsho is to express the characters you truly want to write, the characters that only you can write.

Through the experience and practice of classical rinsho, you will definitely gain something valuable.

Shimauchi 11:42

Let’s keep working on rinsho together and continue to improve our technical skill, sensitivity, and imagination.

This has been Shimauchi from “Shodo Daisuki.”

I’ll keep up my own rinsho so I don’t fall behind any of you.

Let’s meet again in the next video. Thank you very much and see you next time.

About Related Products

Here are the products that appear in this video.

Books / Book & Publication

From complete beginners who are just starting calligraphy to intermediate and advanced learners, the knowledge you can gain from books is invaluable.

In addition to your teacher’s model pieces, books let you study on your own and are perfect for home practice and self-study.

Deepening your knowledge of calligraphy through books will also broaden your perspective and understanding of the art.